IN RICORDO

DI DELARA DARABI

"Gli artisti non dimenticano e nessuna censura sà scoprire dove si nascondono i disegni,gli sguardi furtivi,la memoria e la sete di giustizia"

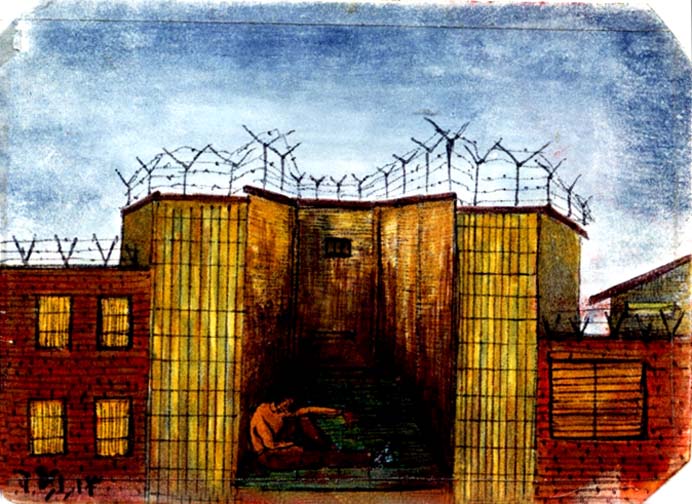

Life inside

Soudabeh Ardavan's prison drawings

Interview by Fariba Amini

September 26, 2002

The Iranian

Soudabeh Ardavan is from Tabriz, a former political prisoner now living in Sweden. She is in her early 40's. She spent eight years of her precious life in the Islamic regime's jail. She is also an artist who drew prison life while she was confined in a cell with other women.

Through these images, drawn from the time she became a prisoner in 1981 until she was released in 1989, Soudabeh tells a story of those horrible days. While in prison, her mother had a stroke because she had thought Soudabeh was among the many executed prisoners; she could not bear the thought of it. She died at age 57, a year after Soudabeh was released.

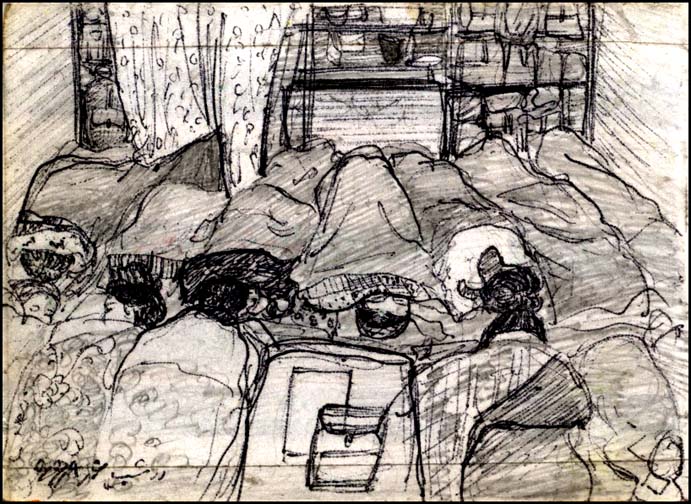

Soudabeh Ardavan speaks of those days. She and fellow inmates were kept in a small cell made for three people, but at times, the cell was shared with as many as 40 prisoners. Sanitary conditions were very poor. There was no proper clothing, and prisoners were given little food and minimum access to the shower. As punishment, prisoners were denied the use of toilets.

Prisoners would sleep on the floor, leaving enough space for the injured who had been severely tortured by guards to get confessions. Soudabeh had not confessed. She was considered a "sar mozei" -- a term used for those who had resisted torture. Those who had repented were called "tavaabin".

Prisoners would sleep on the floor, leaving enough space for the injured who had been severely tortured by guards to get confessions. Soudabeh had not confessed. She was considered a "sar mozei" -- a term used for those who had resisted torture. Those who had repented were called "tavaabin".

She tells her tale, enough to make you shiver. It makes you wonder if it is possible in this day and age, for a human being to be treated with such cruelty only because they were young and outspoken.

She was a university student interested in politics, books and publishing. She was studying architecture and interior design at Tehran's Polytechnic Institute. It was during the Cultural Revolution when the wide-scale crackdown began. The ruling revolutionaries wanted to get rid of "corrupt elements".

She was charged with participating in demonstrations against the Islamic Republic. At first, she was detained, interrogated, and finally, blindfolded on the floor, and sentenced to two years in jail. There was no judge nor a jury or a lawyer. "Islamic justice" did not take more than a few minutes.

It was the most despicable time in the history of the Islamic regime. Interrogation, torture, execution were the order of the day. For the next 8 years, she would be transferred, from Evin to Ghessel Hessar prison, back and forth, from one unit to another, spending time in between in solitary.

She remembers the first time she entered a cell. She thought she had entered a girls school. The prisoners were all young girls, in their teens. Sometimes, there were older women, as old as one's grandmother. They had apparently aided the prisoners or were family members.

Her three famous prison mates were Bijan Jazani's mother; Maryam Taleghani, the daughter of Ayatollah Taleghani, and writer Sharnoush Parsipour.

She tried to write her story through the many pictures she drew. First she hid them for fear of punishment. Then she would get rid of them. Later, she would keep her artwork and somehow smuggle them out. Other prisoners would help her find paper and pencils. She drew her cell mates, guards, life in prison, and cell conditions.

Excepts from my interview with Soudabeh:

I tried very hard, under excruciating conditions and fearing for my life as well as others in my cellblock, to capture moments, horrifying moments and sometimes beautiful ones. I drew pictures of the guards, their faces so cruel, without humanity. I drew pictures of cell mates who had become like sisters to me; their innocence, their youth, their fears.

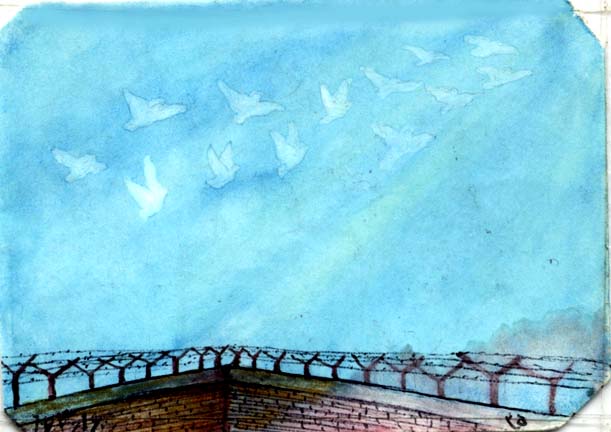

I drew pictures of all of us cleaning the small area we lived in. Or the outside courtyard where we would exercise, when allowed. I drew pictures of the ugly, the unclean, the pure and the blue sky with white birds, hopinng to see freedom one day. I drew everything and anything.

First it was all black and white. I had no colors. Sometimes I would use the petal of a flower or tea to create color. Then someone threw a box of color magic markers through the cell. So I drew color pictures.

I tried to capture a time when evil had taken over all our lives. When the outside world was unaware of the crimes taking place in the jails of the Islamic regime. When revolutionary guards would come to our cells, beat us, flog us, torture us and then leave. And we would ask ourselves why? Why so much inhumanity? Are these people from the same land we have come from?

I tried to capture a time when evil had taken over all our lives. When the outside world was unaware of the crimes taking place in the jails of the Islamic regime. When revolutionary guards would come to our cells, beat us, flog us, torture us and then leave. And we would ask ourselves why? Why so much inhumanity? Are these people from the same land we have come from?

Most of the guards were extremely vicious and used foul language to humiliated us, and destroy us psychologically -- as they had attempted with physical torture. Most of us did not confess and kept our mouth shut. That would make them more furious. Then more floggings and beatings would begin.

From time to time, the head guard would come in. They were two women. They looked ugly and big and extremely rude. They were pros. I was told they were there from the Shah's era. Their names were Bakhtiari and Alizadeh. They would kick us real hard. The Bakhtiari woman wore a soldier's outfit and she would constantly curse us and beat us. She barked like a dog!

Most of the time, in our cell, we did not have to wear our scarves or the chador, only when the male guards would come in. There was the head of the prison, a man called Haji Rahmani. He was huge, quite a character, very vicious. We would be ordered to put our hejab and then he would come in and beat us. I believe he now holds a post in the Ministry of Intelligence.

Sometimes those who had repented -- tavaabin -- would spy on us and at other times they too would beat us. They were the ones who had asked for forgiveness and as a result of their "good behavior" they would be given a special task of making life even more miserable for other prisoners. Sometimes, they would even hold a gun in front of us to frighten us. We were very careful when they were around. We would not talk or say anything in front of them.

Out of the 8 years I was imprisoned, I remember only three months when I felt good. That's when we were taken to a prison block, which had a nice courtyard. There were flowers and trees. And no sign of tavaabin! We felt free, sort of speak. We could talk and walk and socialize without their presence. To some degree, we were not watched and I could breathe a little.

A few months later, when we were once again moved, we heard of the horror stories about the mass executions in prison. In the summer of 1988, right after the ceasefire between Iran and Iraq, there were many prisoners whose terms had ended but werenn't released.

Khomeini had personanlly ordered the male "infidel" prisoners be executed and the women lashed five times a day according to Islamic law. [Amnesty has reported close to 5000 prisoners were murdered in the prisons of the Islamic regime in 1988].

Death sentences were carried out against those who did not repent and beg for mercy. Twenty-five were taken from our cell alone. So many young men and women were amongst them. They were followers of the Mojahedin Khalgh or Fadaian, and many others. I was one of the lucky ones. I was released.

What can I say? The time I spent in prison will never be erased from my memory. So many lives were shattered. So many families lost loved ones. Many parents, facing the loss of their sons or daughters would eventually die from grief. Now, I am trying slowly to build a normal life.

I am studying Swedish and attend art school. I am also working on a book with two other former political prisoners. It is the first time we are telling our stories. A Swedish psychologist and a journalist have also collaborated on this book. My book containing more than 100 prison drawings, will be published by winter 2002.

I am studying Swedish and attend art school. I am also working on a book with two other former political prisoners. It is the first time we are telling our stories. A Swedish psychologist and a journalist have also collaborated on this book. My book containing more than 100 prison drawings, will be published by winter 2002.

I am hoping people will see these paintings and never forget the many innocent lives lost in those years, the many of us whose lives changed forever. The drawings tell a tale of the darkest history in our country.

As for the future, I hope to continue my life without feeling remorse. I am not vengeful. I do not want revenge from my captors. I only hope that one day, those who were directly involved in these crimes will be tried in a court of law and none would ever be able to hold political or governmental office. I do not believe in the death penalty. I want justice to be served but only under international law. And I truly believe that one-day; soon, justice will be served.

You can pre-order Soudabeh Ardavan's book of prison drawings by sending $20 to: Abergssons V 5, 170 77 Solna , Sweden

Send this page to a friendEmail your comments for The Iranian letters section

Send an email to Fariba Amini

0 commenti:

Posta un commento

"Rifiutare di avere opinioni è un modo per non averle. Non è vero?" Luigi Pirandello (1867-1936)